April 22, 2010 (Thursday)

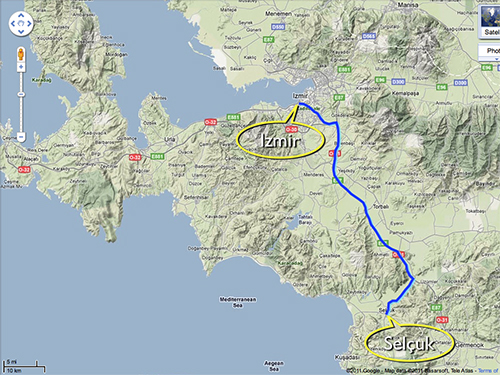

Selçuk. We catch our final breakfast at 8 am on the roof of our pleasant, boutique hotel that took us in after the Crisler Institute housing fiasco when we first arrived in Selçuk late on a Sunday afternoon. Ephesus is a major stop, so we have spent several days here. After breakfast, we get our bags and hit the road for the modern, sprawling metropolis of Izmir. This modern city of several million is built over the ruins of ancient Smyrna, one of the seven cities in the book of Revelation. The drive is pretty easy—good for Jerry.

Izmir (Smyrna). The city of Izmir, or ancient Smyrna, is important to us for several reasons. One is because Smyrna is one of the seven cities of the seven churches in the book of Revelation. Another is because one of the most famous martyrdoms of early Christian history was that of Polycarp (69–155), bishop of Smyrna, who was burned at the stake in the theater at Smyrna. The church father Irenaeus (d. A.D. 202) tells us that in his youth he heard Polycarp speak and that Polycarp had been a disciple of the Apostle John. Thus, Jerry and I are glad to be able to visit this important city of early Christianity.

Once in the major metropolitan area of Izmir, the Garmin actually did find our hotel (with the inflection of Gomer Pyle: “Surprise, surprise!”). The hotel is nice, but as we are checking in, we learn that the air conditioning is not working, so our room undoubtedly will be warm. We get our car parked in the hotel lot and our baggage upstairs. To get a jump on our brief time in Izmir, we immediately put our museum itinerary into action. We decided the most efficient action was to take a taxi to the Archeology Museum of Izmir. As soon as we get in the taxi, the driver tries to sell us a “taxi tour” and shows us pictures of sites, etc. We politely refuse his offer. On the way to the museum, he does stop at a scenic overlook of Izmir’s harbor bay for Jerry to take some nice pictures of the harbor area, including the panorama image immediately below.

Izmir Arkeoloji Müzesi. We arrive at the Izmir Arkeoloji Müzesi in short order and work our way through the displays methodically. We are quite a team now, Jerry taking pictures and dictating information, me following like a shadow recording data and enhancing entries with extra information from museum description plaques next to displays. I have gotten pretty familiar with what catches Jerry’s attention in these museums, and sometimes I even help him “spot” exhibits or artifacts he will find interesting. We view the museum in about 1 ½ – 2 hours. We are learning that every museum, whether large or small, has something unusual to offer. We found the most interesting exhibit at the Izmir museum to be the painted clay sarcophagi. Also, this museum has good representation of items from many of the ancient sites we have visited.

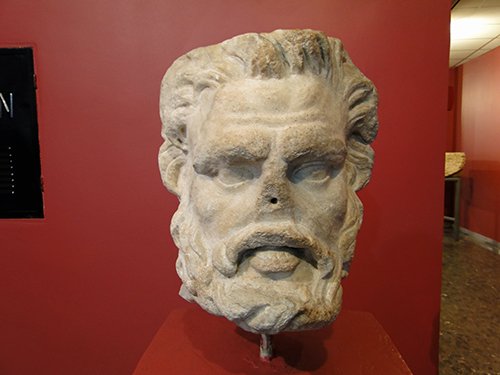

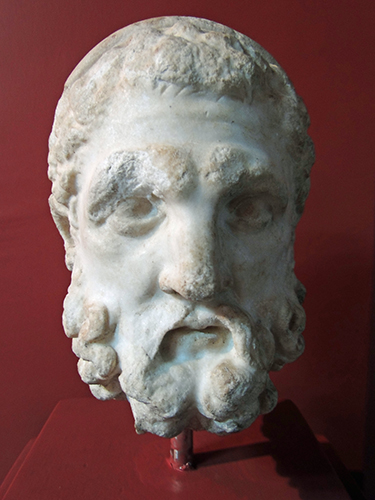

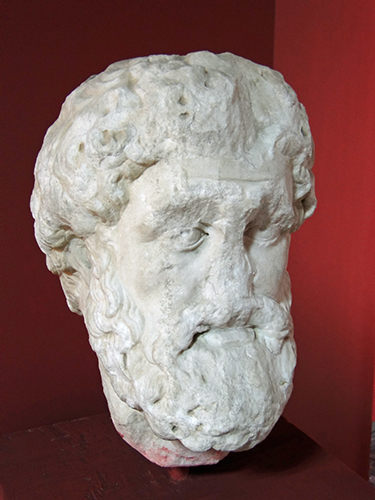

Miletus. The following items are from Miletus. They include classic stirrup vases about 13th century B.C., a statue of a woman about 2nd century A.D ., another statue from 150–30 B.C., a statue of the Hygeia and one of Asklepios about 2nd century A.D., a beautiful mug from the 12th century B.C., and the head of Satryos about 2nd century A.D.

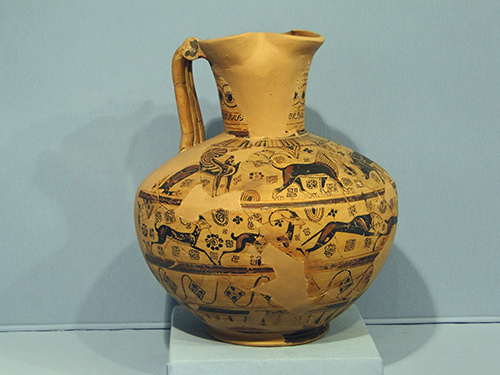

Smyrna. The following items are from Smyrna, which is today’s Izmir. They include a Lebes Gamckos vessel of 580 B.C., statues of a woman and a man about 2nd century A.D., a statue of two girls found in the bouleterion, a rhyton pouring vessel from 6th century B.C., a beautiful oinochoe vessel about 630 B.C., oil lamps found in the agora area, head of a woman about 2nd century A.D., and the head of Athena about 2nd century B.C.

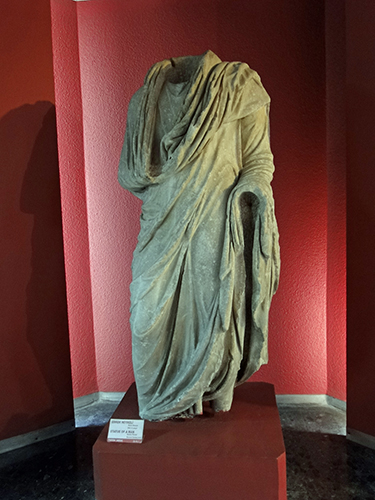

Sardis. This statue of a woman below is from Sardis, which we will be visiting soon. Sardis is one of the seven letters to the seven churches in the book of Revelation. The statue dates from 300–30 B.C.

Ephesus. The museum had a number of items from Ephesus, which we just had left. These included a statue of a woman from 2nd century A.D., an elegant statue of Hera dated 100–200 A.D., a statue of a man about 2nd century A.D., a partial statue in the nude of Dionysios and Satyros about 2nd century A.D., Antinous as Androclos from 138–161 A.D., and a fine relief expertly detailed of Dionysus visiting the Athenian actor Ikarios.

Thyatira. The ancient city of Thyatira represents another of the seven churches that received letters from the risen Christ in the book of Revelation. We will be visiting Thyatira soon. Remains from Thyatira before the Byzantine era are quite rare. The Izmir museum, however, does have a nobleman statue from Thyatira dated 2nd century A.D.

Side. Side today is a modern resort community on the southern coast of Turkey that is adjacent to the remains of ancient Side right on the shoreline. We already had visited the ancient site. The museum at Side was rather small, but had interesting examples of Roman burial practices. Here at Izmir we saw a very well-preserved statue from Side of a priest dated rather broadly from 30 B.C.–A.D. 395

Manisa. The modern city of Manisa is the ancient site of Magnesia. We plan to visit a museum in Manisa that we had missed on our visit in 2002. Here in Izmir, we saw a statue from Manisa of some Roman emperor, dated 2nd century A.D.

Pergamum. We also will visit Pergamum in a few days. Pergamum is another of the seven churches of Revelation. The Izmir museum had the head from a statue of Hercules about 130–150 A.D that was found at Pergamum.

Didyma. The site of ancient Didyma is on the southwest coast of Turkey. The main tourist attraction is the temple of Apollo complex, whose construction never was completed. This head from a statue was found at Didyma and dated 140–160 A.D.

Other Items. Other items in the Izmir museum were not necessarily connected to a particular city, but were of note. Of these, Jerry was most interested in the statue of a Roman imperial priest, which was quite well preserved and illustrates the strength and popularity of the imperial cult throughout Asia. A chair with griffin sides and winged back caught Jerry’s attention, since this was a seat of honor from either a theater or a bouleterion Jerry surmised. The clay sarcophagi were unusual, since we had not seen many, and in fantastic condition. The intricate artwork was impressively executed with geometric precision. Ornaments and medical instruments from the 1st–2nd century A.D. were right in our target date range. A nice mosaic was displayed on a wall. A old example of a lekythos vessel was from the 6th century B.C. A grave urn, burial figurines, and burial offerings all were dated to 1st century A.D., so Jerry studied them closely. Finally, Jerry said the display showing all the basic shapes of ancient containers and their names and descriptions of use was the best he had seen anywhere.

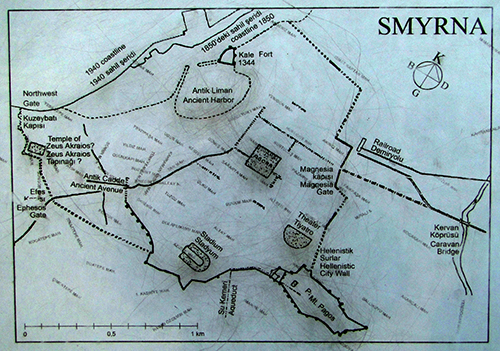

Roman Agora. After the museum, we caught another cab over to the Roman Agora. (This taxi driver also tries to sell us a taxi tour.) We had visited the Roman Agora in our previous visit to Turkey on the last sabbatical. Roman agoras were built as the hub of the ancient city. Here is where all administrative, commercial, political, and judicial business was conducted. Alexander the Great originally had built the Smyrna agora, but almost all of those structures were destroyed in the devastating earthquake of A.D. 178 that nearly wiped out the city. Generous help from the emperor, Marcus Aurelius, and his wife, Faustina, were crucial to the rebuilding of Smyrna, and what remains to be found today date to this Aurelian period after this earthquake.

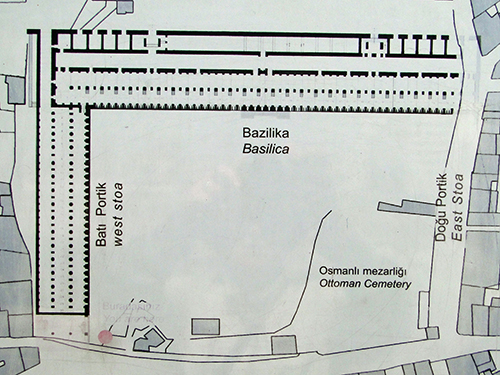

The agora is quite changed from our visit in 2002. The ticket office/booth area has been remodeled and upgraded. Flowers are planted in the entrance area near the ticket booth, etc.—much nicer. Nearby, a schematic of the site now assists visitors in the layout of ancient Smyrna as well as the location of the agora in the city plan. Another schematic shows the ancient agora itself, with the two major remains of the West Stoa and the Basilica area.

West Stoa. The West Stoa of the ancient Roman Agora at Smyrna presents the bulk of what is to be seen on the site today. On the ground level, the Faustina Gate on the west side represents the main entrance to the ancient agora and has been erected since we were here in 2002. The keystone of the gate has a relief of the bust of Faustina, the wife of the emperor Marcus Aurelius who was instrumental in the rebuilding of the city after the great earthquake of A.D. 178. The only columns erected on the site are a part of the west portico of the agora along a line parallel to the West Stoa support arches of the basement below. The subterranean vaulted arches viewable today supporting the three-story superstructure of the agora represents what we would have considered the basement of the complex, housing water pipes and access to all parts of the agora. Some of the terra cotta piping system is still viewable today, and a fresh water fountain still supplies water to this very day (incredible Roman engineering). The Roman Agora of Smyrna is one of the few places where the visitor not only can see, but also is allowed to walk in this subterranean basement of an ancient agora, which is very neat.

Basilica. The Basilica area is perpendicular to the West Stoa on the north side of the site. Roman basilicas were multi-purpose rooms usually found on one side of an agora where speculators, businessmen, banking and other activities were conducted. The basilica at Smyrna is completely intact, although currently you are not allowed entrance. This area also has a run of the subterranean vaulted support arches, similar to the West Stoa, and you are allowed to walk in this basement area. Archeologists have set up an inscription that apparently was a part of the ground-level columned portico.

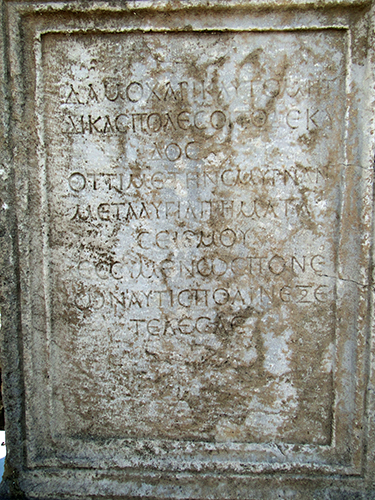

Earthquakes. The history of ancient Smyrna, as for many cities of Asia, is defined by earthquakes, which were not uncommon in this region of Turkey in ancient times. One particularly devastating earthquake in A.D. 178 required huge resources and finances for rebuilding Smyrna. The inscription below is to honor one major benefactor and patron of the city. The inscription reads: Praise to Damokkaris O Judge Damokkaris, famous with his skill! This success also belongs to you: After the awful (mortal) disasters of an earthquake, with very diligent work you succeeded in the making of a city out of Smyrna again.

Open Square. We look over the whole site of the open square from ground level. The archeological remains of excavation are gathered and stored in sections of the open square, apparently grouped by common connections. We do not know if plans include assembling these remains as a part of their original location and purpose. We also saw a pretty woodpecker while there. As we were walking the grounds of the open square, Jerry spotted a beautiful brown woodpecker on the gravel road. Jerry used his zoom lens and just barely caught a picture before the bird took to flight and disappeared.

Turkish Walking. When we were done, Jerry asked the ticket agent about getting a taxi to our hotel. The man says the hotel is “not far, and you can walk it,” which, we are learning, distance suitable for walking in Turkey is a matter of opinion. Evidently the Turks walk everywhere, so nothing is “too far” in their estimation. A man was walking by, and the ticket agent spontaneously subpoenaed the man to walk us part way to our hotel so we wouldn’t get lost, and the man agreed to do so. As usual, we find that the Turks are most hospitable. “Not far” means something entirely different to us than to the Turks. In fact, the hotel really “is far.” When we reach a street that is the main avenue of our hotel, we thanked our temporary guide, and he takes his leave.

We finally get back to our hotel, and the room is warm, as we suspicioned. While looking out the window across the busy boulevard, we saw some men across the street about 5 stories up trying to hand off a Turkish national flag from their office window to an adjacent office window. They were attempting to string the flag for display. The flag is huge. They had great difficulty throwing a string attached to the flag from window to window. Funny scenario. After taking showers and cleaning up for our evening out with friends in Izmir, I take a little nap while Jerry sets up his “charging station” for all his electronic gadgets.

Izmir Harbor Dinner. We get ready for our dinner with Levent, our Turkish travel agent who helped me with some of our accommodations, and Dr. Mark Wilson, founder and director of the Asia Minor Research Institute, who is an American but lives in Izmir. Levent and his wife, Natalie (from Ukraine), picked us up at 6 pm. Natalie is learning English. They take us to a mall area by the harbor to an Italian restaurant right on the water. (The owner is a friend of Levent’s.) Very picturesque area, and we sit outside to enjoy the view, even though the air temperature is pretty cool. We enjoyed an appetizer while waiting for Mark and Dindy Wilson, who arrived about 10 minutes later. We find out that Mark and Dindy live in the central city of Izmir and take public transit everywhere—thus, the late arrival. Dindy is very outgoing and I like her a lot. Mark is more reserved and very nice about answering my questions about Roman roads and travel from Antioch of Pisidia to Attalia. Mark estimates Paul could have done the journey in a week, but to me that amount of time still seems very fast—I must do some research on Roman road travel. We have wonderful gelato for dessert. The sun sets while we are dining, and the harbor view is gorgeous.

We finally get back to the hotel around 9 pm after a very nice evening. We learned from Dindy that the flags being hung all over the city were in connection with a national children’s holiday tomorrow, so now we know why those men were trying so desperately to hand the flag to each other outside the building. (You might pick out several of these huge flags on the sides of buildings in the background of the harbor shot above.) Back at the hotel, I try to give Angela a call but missed her (our NOBTS student who is house sitting for us). However, I was able to reach mother and talk to her for a bit.

For a video of the Izmir (Smyrna) action today: