Europe & Turkey—Day 25: Manisa, Thyatira, Pergamum

Posted by DrKoineApr 24

April 24, 2010 (Saturday)

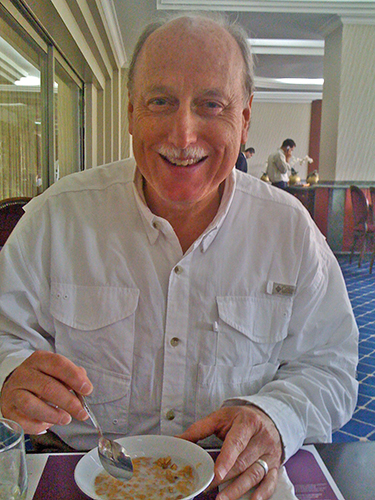

We slept a little later this morning, since the Manisa museum we are here to visit does not open until 9 am. Breakfast is good, with omelets and cereal. The spoons they give you for cereal are as large as serving spoons! After breakfast, we get our bags and luggage and check out.

Manisa Museum. The Garmin leads us straight to the museum! What irony this rare success with the Garmin turns out to be that the Garmin for once gets us straight to a museum. Why? Well, the only time the Garmin gets us straight to a museum, we will be hugely disappointed.

Manisa Mosque. We were confused at first by the large mosque to which the museum is immediately adjacent. At first, we think the old mosque has been converted into the Manisa Museum. After Jerry explores the block, though, he is convinced the building actually is a functioning mosque.

Museum Entrance. Jerry finally finds the museum’s entrance gate. Walking all around the entire block, he discovers what looks almost like an alleyway off to the side of the mosque, but that is the museum entrance! We step in and see a ticket booth just inside and to the left of the entrance gate.

Museum Status. We go to buy a ticket at the ticket booth, but we are told the museum is closed for renovation!! Closed?? At dinner last night on the harbor at Izmir, Mark had told us that, after a serious theft a year or so ago, the museum curator had “put away most items worth seeing,” such as the original and famous, unusual eagle table from the synagogue in Sardis. We still wanted to see what there was to see in the museum. Unfortunately, Mark didn’t know that the museum also was closed. The caretakers at the ticket booth had indicated the reason as “closed for renovation,” but we saw absolutely no evidence whatsoever of any renovation work going on anywhere—for quite some time, if ever! We conclude this place must be closed indefinitely, perhaps even for years—who knows with labyrinthine governmental bureaucracy?

Museum Misery. What a disappointment! The museum at Manisa was the second most desired item on Jerry’s to-do list for the trip, and the only one specifically mentioned in his Lilly grant application. So, the great irony of this sabbatical travel has been that the top two items on Jerry’s list for the trip—seeing the gladiator burial grounds at Ephesus and researching the museum at Manisa—were a complete bust. I can tell immediately that Jerry is devastated—I mean, really devastated. That persistent, mischievous twinkle in his eye vanishes. I feel terrible for him. We are finding that the hardest part of any research of museums in Turkey is getting accurate information! No one had said a new museum was under construction in Miletus, yet we found an almost complete new building out just as we were leaving that site. (For a reminder of that visit, click here.) Not even the Turkish government website says anything about the Manisa museum being closed (and certainly no official admission that this closure most likely means closed indefinitely for the foreseeable future as far as we can tell). Ugh!

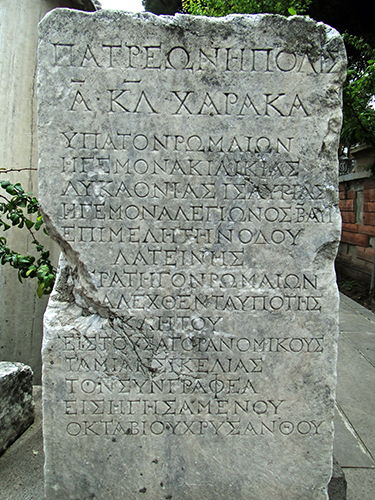

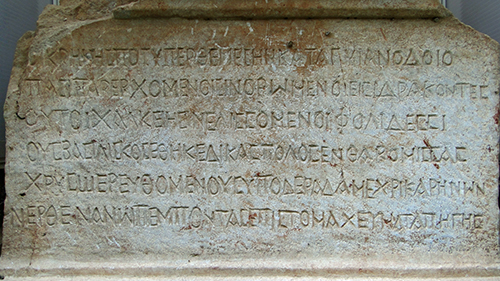

Courtyard Tour. Jerry has a dogged determination. His self discipline is intensely focused on meeting goals. That is to say, he is one determined old cuss. I can see him forcing himself to move on through the disappointment with a set jaw for the rest of our day and the trip’s itinerary. After being stunned temporarily by the unexpected and unpleasant news of the museum’s closure, Jerry pushes himself into action. He asks permission, and we are allowed to look around in the garden/patio area where some artifacts are lying around, including statuary and inscriptions. Jerry takes pictures. We do find some interesting items. Later in the day, when we toured the museum at Bergama (ancient Pergamum), we took some consolation in being able to see items that came from Manisa, including four grave stele, an osthotec (a small box for holding the bones/ashes of the dead), and inscriptions. Here are a few pictures of the courtyard and its items of the Manisa Museum.

Jerry says this inscription below is about the worship of the the revered god, Apollo. The emperor Domitian liked to compare himself to Apollo, and scholars speculate the name for the king and ruler of the Abyss in Revelation, “Apollyon” (Rev 9:11), is a play on words for this connection to Roman imperial propaganda.

This Roman sarcophagus has the traditional Medusa head on the side. The representation was intended to ward off evil spirits.

This closeup below shows a word that appears often on grave stele and grave memorials. The word is chaire, which is akin to our “Farewell.” This is the goodbye to the deceased loved one.

This grave stele below with a relief depicting family members records an epigram for Asklepiades and Stratonike (Demirei). The date is 2nd century B.C.

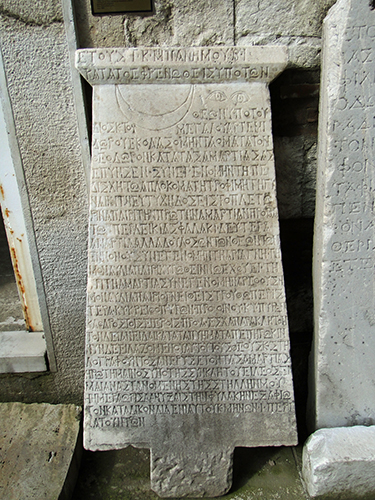

The following inscription, dated A.D. 235–236, is an elaborate confession to Zeus by a man whose name was Theodoros. In the confession, Theodoros calls himself a “sinner.”

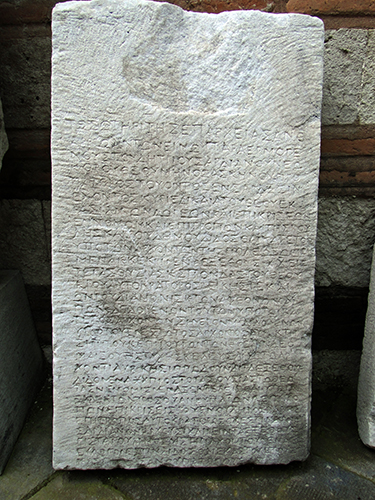

The following inscription is a record of the letter of a priest from Sardis to the proconsul of Asia Minor written about A.D. 188–189. Although almost a hundred years after the book of Revelation, this letter illustrates the continuing strength of pagan and imperial worship in the very area where the seven churches of Revelation were located.

The following relief memorializes four named gladiators. The first two names are Hermes, and Kuros, but Jerry could not quite make out the names of the other two.

The following inscription is an “honorific,” that is, a decree by the people of Mysia Abbatis (Gordes) dated 130 B.C. to honor a leading citizen or public official, probably for some special public benefaction.

The inscription below is written in small but very neat letters and records the testaments of Epikrates (2nd or 3rd century A.D.). The inscription is written on both the front and back sides of the monument.

This image below of a military officer and his attendant is a relief inset closeup from an honorary inscription by the Lakimenoi, Hodenor, Mokadenoi, and Ankyranoi (Demirci) sometime after 129 B.C. The soldier is depicted in standard military parade dress. Jerry was not sure, but the very small figure on the left could be either a dependent heir of the military nobleman or possibly a conquered people. The small proportions would be appropriate for either the dependent heir or as a sign of humiliation for the conquered. The relief has been defaced; the individual faces have been scratched into anonymity and the head of the smaller figure knocked off.

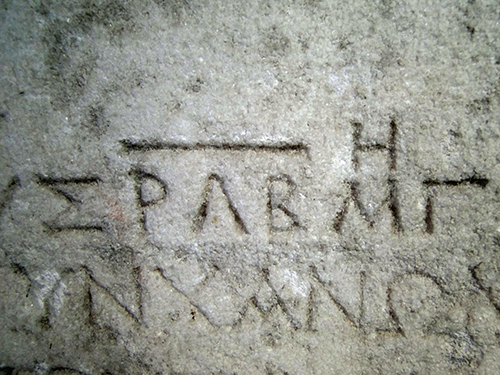

Jerry was fascinated with the following incomplete inscription. He had read that the process of preparing a stone for an inscription included scoring the stone with parallel lines that later were erased when the inscription was finished. However, he never had seen these scoring lines before. Because this inscription was not completed, the light scoring lines are still visible. This image was a pleasant surprise and find for him. Yea!

Jerry forced a smile for our traditional self portrait at the museum entrance. He is a real trouper.

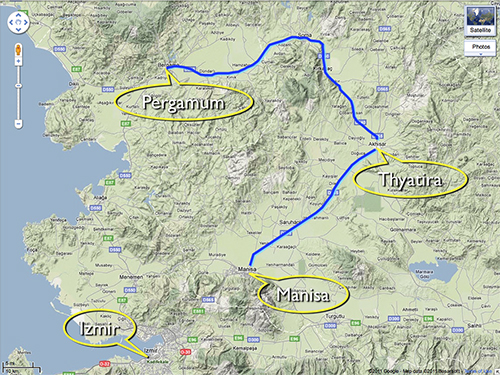

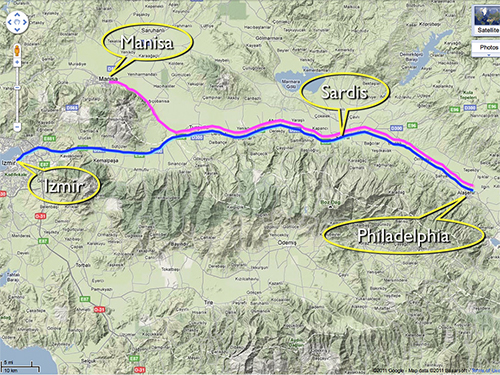

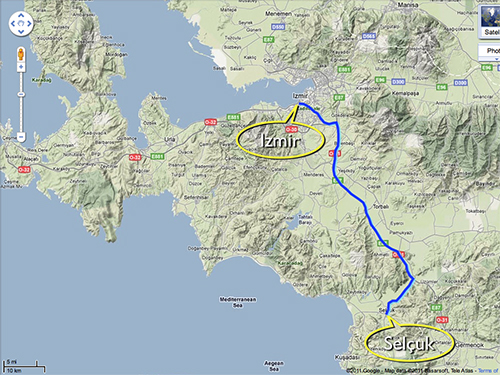

Ahkisar (Thyatira). We leave Manisa and head to our next destination for the day, Ahkisar, which is ancient Thyatira, one of the seven churches of Revelation. The Garmin is some help in putting us in the right direction.

Sehir Markez. Modern Ahkisar is actually quite large, a busy city with lots of traffic, pedestrians, and one-way streets. Jerry has a hard time negotiating the congested downtown area. We head toward what looks like central city and then see a sign to “Sehir Markez.” Jerry guesses this means something like “downtown market” and heads that direction. We drive right up to the site of ancient Thyatira, which is a whole block in the middle of the Ahkisar market district! So the modern market literally is right on top of the ancient market! Our problem is, in this crowded, busy downtown business district—where to put the car? We drive around the perimeter of the excavation several times looking for a place to park, but the area is jammed. We finally find a place to park on the street about a half block from the site of the excavation area. We decide that I should wait with the car to be sure it’s okay. Good decision. A “meter man” comes by shortly after Jerry has left and asks me for 2 TL to pay to park, which I pay and get a ticket for the windshield to show we paid. I actually have fun people watching and observing the “regular” routine of downtown Ahkisar.

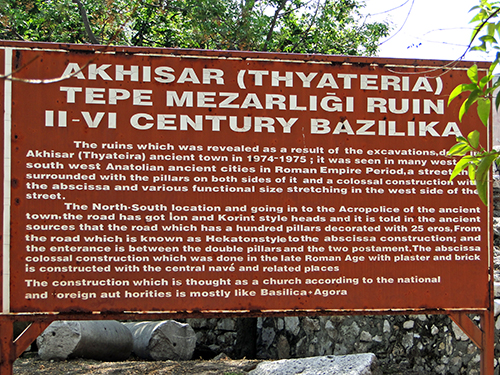

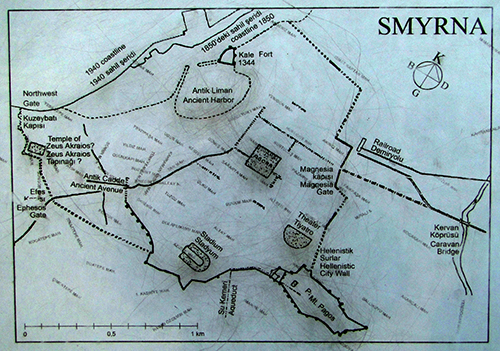

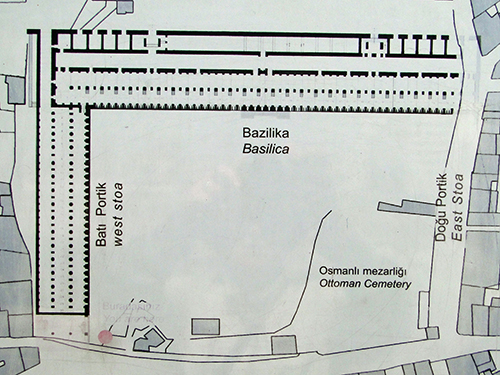

Ancient Thyatira. Jerry walks back up to the site of the excavation and pays the small entrance fee at the gate. I saw him disappear beyond the gate to explore the site. The original excavation work was done in the 1974–1975 season. As was typical in Roman Anatolian cities, the main street into the downtown area was collonaded on both sides of the street with 100 columns topped with Ionian and Corinthian captials, interspersed with 25 statues or reliefs of Eros. The surviving basilica, which shows the area excavated was in fact the ancient agora, or market, dates to the late Roman age, but only the brick superstructure remains of the original marble façade. When he got back Jerry said that he had gotten some good photos and a movie. Yea! Success! I can tell he is a little encouraged actually to find the archeological site of ancient Thyatira in the middle of a busy Turkish city. The faint hint of that twinkle in his eye seems to return.

Bergama. Our third and final destination for this busy day is Bergama, which is the modern city next to the acropolis of ancient Pergamum. Pergamum is another of the seven churches of Revelation. Road construction made the drive to Bergama difficult and dusty! As we are getting closer to Bergama, Jerry commented that from now on he’ll always think of dust when he thinks of Turkey—to which I spontaneously replied, “Yeah, if I were still a child who liked to eat dirt, I’d be in heaven.” We both laughed so hard that Jerry had tears in his eyes and could hardly drive! I guess I’d better not be so funny. But dust and dirt are ubiquitous with Turkey!

We get to Bergama, and, surprise! The Garmin can’t find anything. Yet, Jerry (alias “Radar”) follows his nose straight to the museum! Not one wrong turn. How does he do that? We parked across the street, checked the museum hours, and then had a little lunch in a line of small bistro restaurants across the street from the museum entrance. The museum is open until 6:30 pm, which is later than other museums typically and gives us time to get lunch. OPEN is a very important word in Turkey.

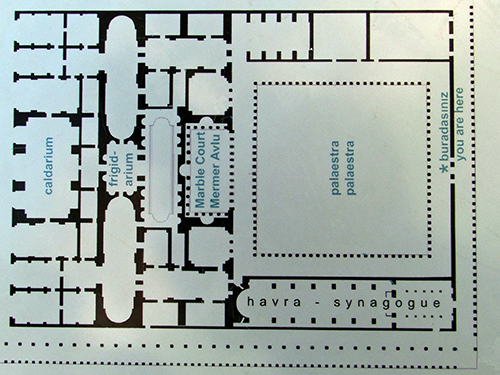

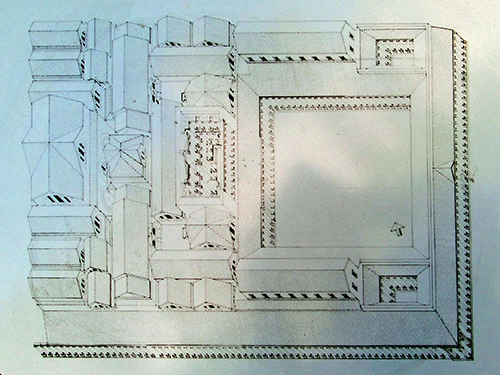

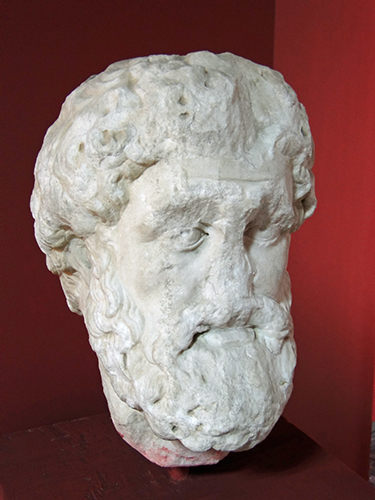

Bergama Museum. We get lunch at one of the little bistros. After eating, we record the Thyatira pictures there at the restaurant, because I had not been with Jerry to make records as he was shooting away like I normally do. We then went back across the street into the Bergama museum. The museum has some new additions since last we visited in 2002. So sad to me that they only have a model of the altar of Zeus and a piece of one horse from a relief—The Pergamon Museum in Berlin has it all, and the reliefs on display in Berlin are so beautiful. In the Bergama Museum, a new room for Islamic culture has been added, which is very similar to the display in Antalya. Our museum visit is about 3 hours. Jerry had me record the following information from a nice description of the ancient Pergamum School of Sculpture.

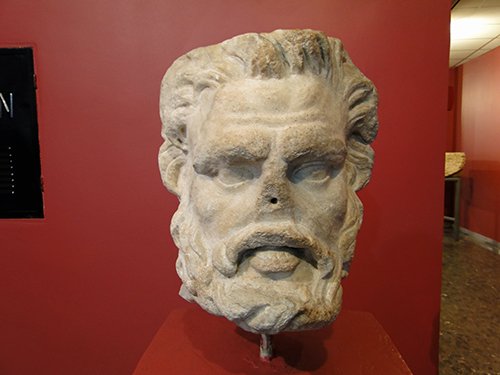

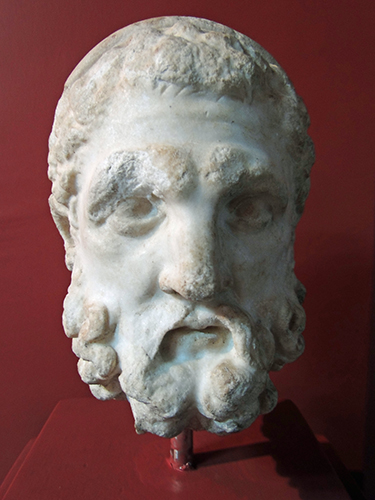

Pergamum School of Sculpture. The ancient city of Pergamum politically and economically was a powerhouse in the Hellenistic period of Anatolia and a leading city in science and arts. This distinction in science and arts was energized by the Pergamenese kings’ interest in science and arts and support of artists. As a result, Pergamum developed a strong tradition as a cultural center. In style they absorbed 4th century Greek realism and naturalism that replaced the 5th century grotesque style. In this new style, the gods were depicted with personality and natural body movement–vivacious figures with facial expressions–all closer to reality. Specific features of this style included detailed body anatomy, but exaggeration on muscles, with a richness of motion, yet severe and sharp manner of the body. Body motion was suggested by shadows in drapery. Facial expressions sometimes were exaggerated to reveal emotions; the most common was suffering. Related emotions commonly depicted were excitement and enthusiasm. Male hair often was disheveled, with a strong contrast of light and shadow by carving deep parts in the hair.

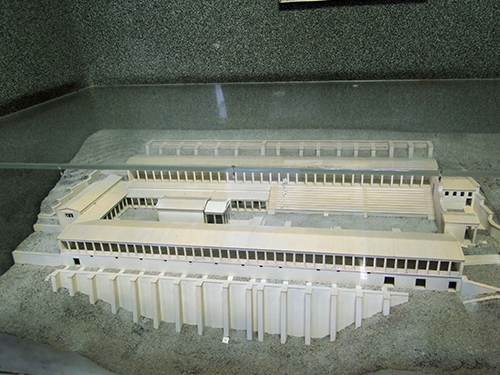

Significant examples of this Pergamum style are the bronze statues of Galatians ordered by king Attalos I to commemorate his victory over the Galatians. While we do not have the originals, we do have marble copies from a later period. The famous Altar of Zeus is the most important work of the Pergamum school, which also was in remembrance of the battle against the Galatians. On this altar, the scenes depicted in the gigantic friezes in high relief symbolized Pergamum’s foundation myth, especially in the inner friezes of the altar. Their foundational myth is the story of Telephoros. This monumental Altar of Zeus does not reside in Turkey. German archeologists spirited the original material to Germany, which is now housed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. (For our visit to this museum earlier in this trip overseas, click here.) Portraits also have an important role in the Pergamum school. The most renowned is the famous Bust of Alexander that now resides in the Istanbul Archeological Museum.

Museum visitors are looking at the description of Pergamum’s great Altar of Zeus with black and white photos of the original friezes that are reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. We were sad that all the Turkish people had to see of their own archeological artifacts were black and white photos from a museum in another country. A model of the altar is in the left foreground of the picture. (For a link to the blog on the Berlin Pergamon Museum, click here.)

The image below is a model of the Trajan temple complex that sat on the very top of the Pergamum acropolis. We will visit the temple site tomorrow. The temple illustrates the strength of the imperial cult religion and provides background for understanding the context of the letters to the seven churches in Revelation.

Torso of a man in Roman armor found at Pergamum. Probably imperial.

This table leg of the Hellenistic period is from the Pergamum acropolis. The artifact was found in the house of the Consul Attalos.

Roman sundial. This one is similar to the one we saw in the museum at Side. (For a link to the Side blog, click here.)

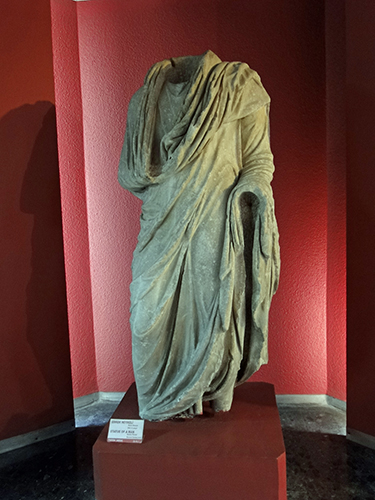

A statue of the emperor Hadrian in the Greek “heroic” style (in the nude). The statue was in the library at Asklepion (the famous healing center associated with the god Asklepios that was adjacent to ancient Pergamum). The toga of the nobleman is draped over the left arm, and the military dress of the general is next to a missing right arm.

A finely-executed statue of the goddess Fortuna discovered in the lower city of Pergamum.

This Roman sarcophagus is from Kestel. Besides the traditional Medusa heads, the relief indicates a person of equestrian rank.

The museum has a nice display of Roman pottery from various periods.

We saw more children’s play stones than we’ve seen anywhere. They are approximately the size of nickels and dimes.

The museum has an osthotec from Manisa. An osthotec is a small box for holding the bones and ashes of the dead. The garland and bull denote sacrifice.

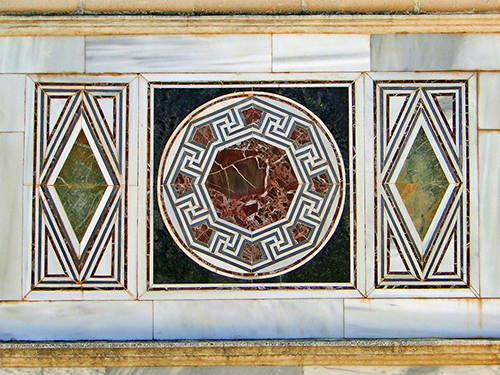

This Medusa head mosaic is very similar in design to the one that we saw at the museum at Corinth in 2002. This mosaic is approximately 4.20 x 4.45 meters.

Below is a display of medical instruments, probably associated with the Asklepion that was near Pergamum. When he sees these kinds of archeological artifacts, Jerry says he always thinks of the New Testament description of Luke as “the beloved physician” (Col 4:14).

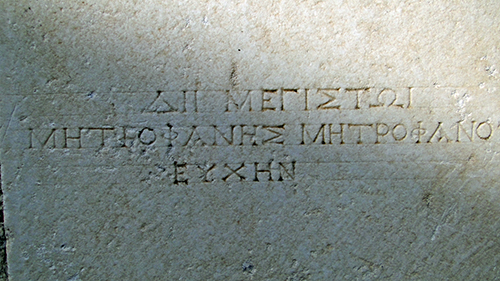

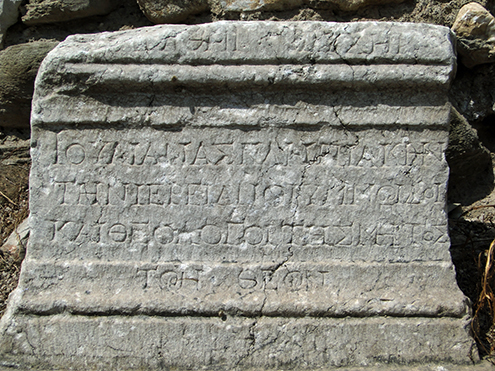

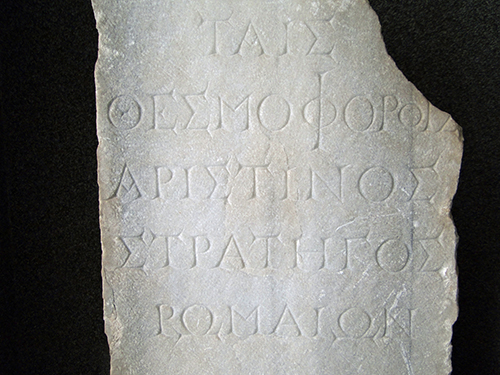

The votive inscription below is from the Demeter Sanctuary of Pergamum. Jerry says the dedication is to Aristinos, who was a Roman city magistrate, or local provincial official.

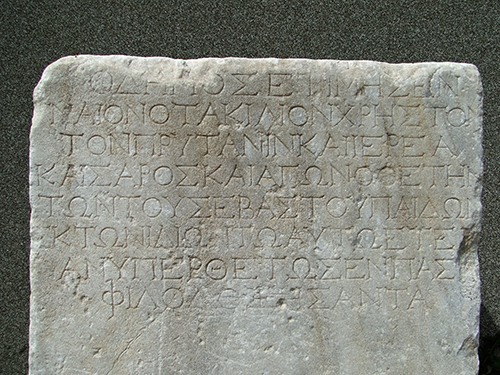

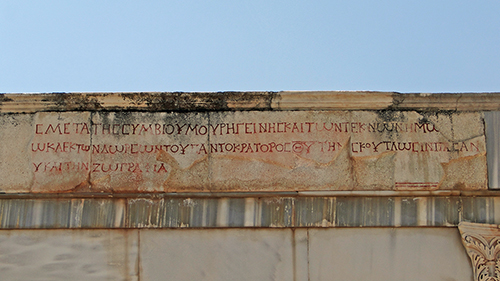

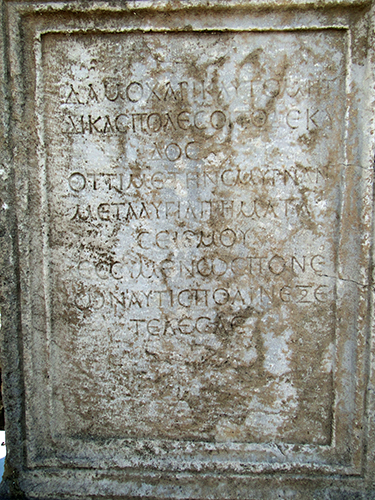

This image is another Roman honorary inscription. The honorarium was found in the theater area and dates from 37 B.C. to A.D. 14 during the reign of Augustus.

Another honorary inscription is from the theater area, dated a little later to A.D. 114–123, that is, somewhere toward the end of Trajan’s reign and into the reign of Hadrian.

The head below is a copy of the famous Pergamene Head of Alexander the Great. The original is in the Istanbul Archeological Museum.

Another item from Manisa is a grave stele of Greco-Persian origin. The traditional royal lion hunt is displayed.

We saw a whole series of grave stele and osthotecs from Manisa.

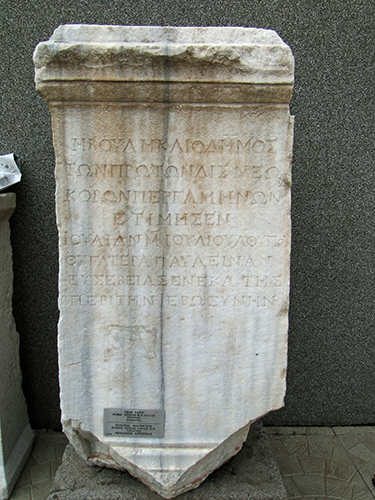

Wall insets house four grave stele of Roman origin from Manisa. Jerry thinks the inscription on the stele on the far right has a mistake, but to be sure, he needs to research this later when he has time. A closeup follows of this supposed mistake, and then an image of the second stele from the left, which is the nicest of the four.

The museum has a very nice assembly of Roman glassware. These small and delicate pieces probably were used to hold oil and ointments. Even thousands of years later, one can imagine how subtle and beautiful the original colors were.

This gladiator stele was found in the Roman basilica area (commonly called the “Red Hall”). The relief shows one particular aspect of fighting with wild beasts. Paul uses the imagery of fighting beasts as a strong metaphor of his missionary struggles in Ephesus (1 Cor 15:32). (Some speculate that Paul literally might have been subjected to beasts in the theater at Ephesus, but this scenario is highly unlikely.)

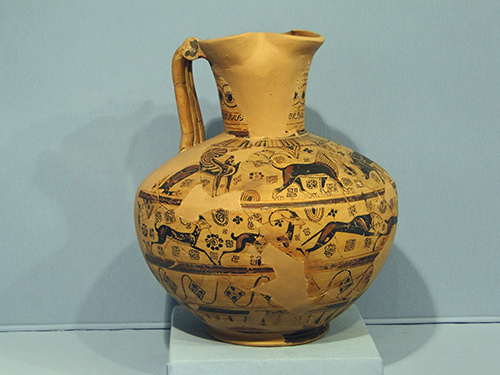

Pottery from the Greek Archaic Period is on display. The geometric designs and shapes are traditional.

Votive offerings were made at the Asklepion near Pergamum for healing received. The part of the body healed was the typical form of the offering. The votive below apparently was for the healing of an ear or for the sense of hearing. The inscription reads, To Asklepios, Savior, Fabia Secunda, according to her strong desire.

Jerry called this wing “the bronze room,” because almost all the display cases had bronze objects. Most of the objects were Roman of the Early Bronze period. The following image is a bronze statue of a soldier.

The museum, of course, had a display of the typical oil lamps one sees everywhere, but this lamp below is distinctive in design and incorporates two lamps together.

This relief depicts Demeter making a typical sacrificial offering. The Roman relief is from the terrace level of the Pergamum acropolis.

Jerry was fascinated with this piece. He is not sure of the exact nature of its description as a “corner acroterium,” but the 2nd century artifact is from the Asklepion.

The coin exhibit is limited. The bee image hails from Ephesus, dated about 387–295 B.C. The poorly preserved Seleucid coin is Antiochus III, dated about 222–187 B.C.

The chariot relief below has fine detail, but the accompanying inscription is incomplete. Jerry speculates this might be a depiction of the sun god, Helios (Roman: Sol), in his traverse of the heavens. Note what appear to be sunbeams emanating from the hands. The horses’ hooves look to be trampling upon a serpent. Jerry says the identification would be stronger if the imagery had four horses; traditionally, Helios had four steads (Pyrois, Aeos, Aethon, and Phlegon).

One rarely sees the actual molds that were used to create iconic impressions. The image below shows a ceramic mold used to make such impressions.

The Roman statue below represents the mythological creature, Centaurus, who had the torso, head, and arms of a man, but the body of a horse. This statue was found in the Asklepion.

The following inscription is dedicatory to the emperor Caracalla (198–211). He is honored as “Father of the City.”

A jewelry display included bracelets, necklaces, and beautifully detailed gold earrings.

Iskender Hotel. After finishing the museum, we got to our hotel, the Iskender, where we’ve stayed before, and check in. The room is nice enough, and best of all for Jerry, two oranges and a knife to peel them await him on the table! We discover that wifi works in our room with no password needed, and we called several people: Robert Comeaux, Cindy, Pops, Janice. We eat in the hotel restaurant, and it’s okay, but nothing to write home about. Then, we use the hotel Internet computer to check email, etc. Tomorrow we’ll be heading to the Pergamum acropolis right on the edge of modern Bergama.

For a video of the Manisa, Thyatira, and Bergama action today: